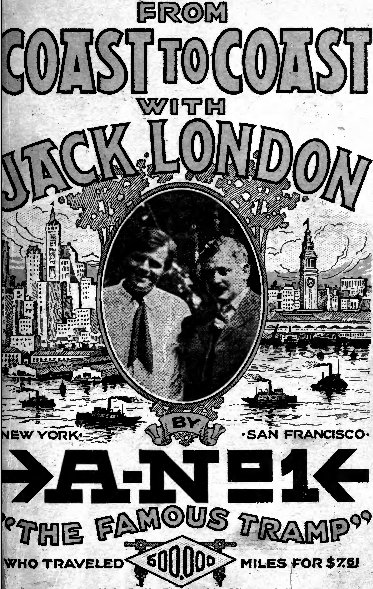

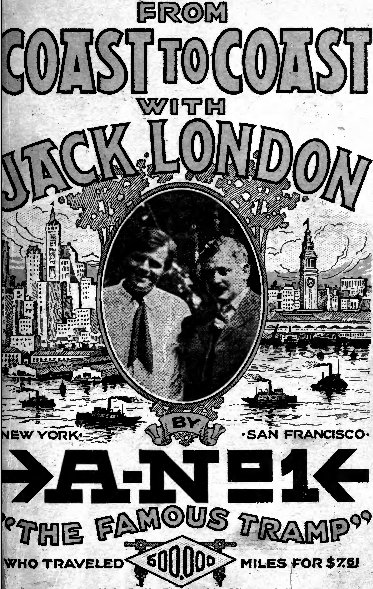

FROM

COAST TO COAST

WITH

JACK LONDON

BY

->A-No1<-

THE FAMOUS TRAMP

WRITTEN BY HIMSELF FROM PERSONAL

EXPERIENCES

SEVENTH EDITION

PRICE, 25 CENTS

COPYRIGHT 1917

BY

A-No. 1 PUBLISHING COMPANY

All subject matter, as well as all illustrations,

and especially the title of

this book, are fully protected by copyrights, and

their use in any

form Whatsoever will be vigorously prosecuted for

Infringement.

THE

->A-No1<-

(TRADE MARK)

PUBLISHING COMPANY

ERIE, PENN’A,

U. S. A.

To restless young men and boys who read this book,

the author, who has

led for over a quarter of a century the pitiful and

dangerous life of a

tramp, gives this well-meant advice:

DO NOT jump on moving trains or street cars, even

if only to ride to the

next street crossing, because this might arouse the

“Wanderlust,”

besides endangering needlessly your life and limbs.

Wandering, once it becomes a habit, is almost incurable,

so

NEVER RUN AWAY, but STAY AT HOME, as a roving lad usually

ends in

becoming a confirmed tramp.

There is a dark side to a tramp’s life:

for every mile stolen on trains,

there is one escape from a horrible death; for each

mile of beautiful

scenery and food in plenty, there are many weary miles

of hard walking

with no food or even water through mountain gorges

and over parched

deserts; for each warm summer night, there are ten

bitter-cold, long

winter nights; for every kindness, there are a score

of unfriendly acts.

A tramp is constantly hounded by the minions of the

law; is shunned by

all humanity, and never knows the meaning of home and

friends.

To tell the truth, the “Road” is a pitiful

existence all the way

through, and what is the end?

It is an even ninety-nine chances out of a hundred

that the finish will

be a miserable one—an accident, an alms-house,

but surely an un-marked

pauper’s grave.

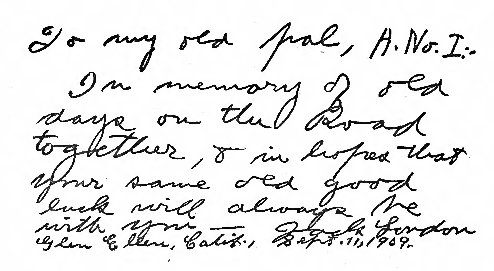

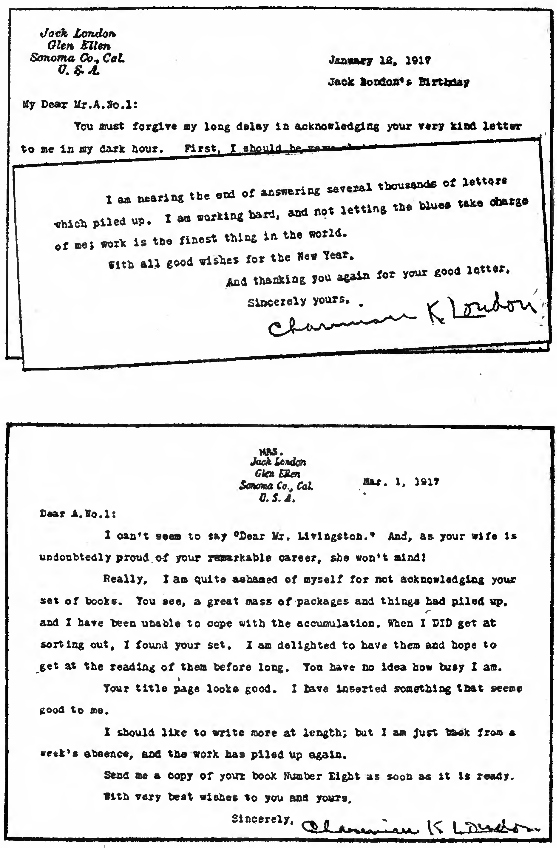

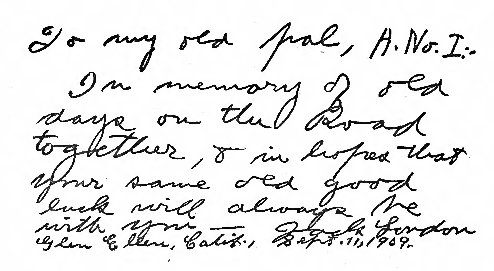

To

JACK LONDON

Of all good fellows I’ve met, the best one,

and

MRS. JACK LONDON,

His greatest pal

and

Author

of

“THE LOG OF THE SNARK”

The book everybody should read.

Contents

OUR ADVENTURES FIRST The Meeting of the Ways SECOND The Smoky Trail THIRD In the Thick of the Hobo Game FOURTH Hyenas in Human Form FIFTH The Hoboes’ Pendulum of Death SIXTH The Killing of the Goose SEVENTH Shadows of the Road EIGHTH Old Strikes & Company NINTH Deadheading the Deadhead TENTH Sons of the Abyss ELEVENTH The Rule of Might TWELFTH Prowlers of the Night THIRTEENTH Bad Bill of Boone FOURTEENTH Old Jeff Carr of Cheyenne FIFTEENTH Sidetracked in the Land of Manna SIXTEENTH The Parting of the Ways

“The Meeting of the Ways.”

“Infamous is your assertion that in New York City should be abroad even one resident so grossly uninformed of the miserable existence led by the roving tramps as to voluntarily offer himself as a travel mate to a professional hobo, A. No. 1!” Editor Godwin of the Sunday World Magazine protested, having overheard a corresponding comment I had broached to a reporter who was recording the points of an interview.

On arriving in New York City I had drifted to the editorial rooms of the newspaper publishing the best feature section in connection with its Sunday issue. The World had accepted my proffer to furnish an exclusive interview. A pencil pusher was assigned to take notes of my story which he was ordered to transcribe into a human-interest article for the magazine section.

Most entertaining was the tale of hobo life which I had to unfold. It reviewed an existence fairly brimming with adventures and experiences the like of which were never encountered by folks who trailed in the well-beaten ruts of legitimate endeavor. Of paramount importance was the circumstance that securely pasted in a memorandum I carried on my travels documentory evidence which verified the fact that my statements were based on actuality.

To this day when the possession of a most happy home seems to have effectually quenched the spirit of unrest which heretofore had driven me for more than thirty years over the face of the globe, I still treasure the humble note book as my most cherished belonging the only relic remaining to remind me of the days I wantonly wasted on the Road.

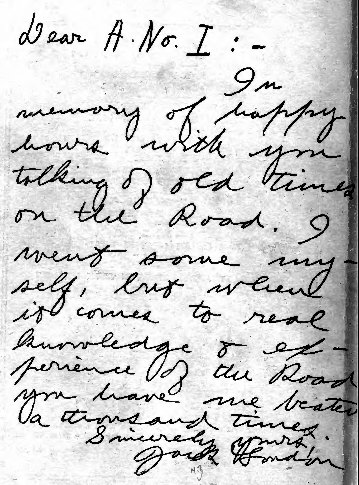

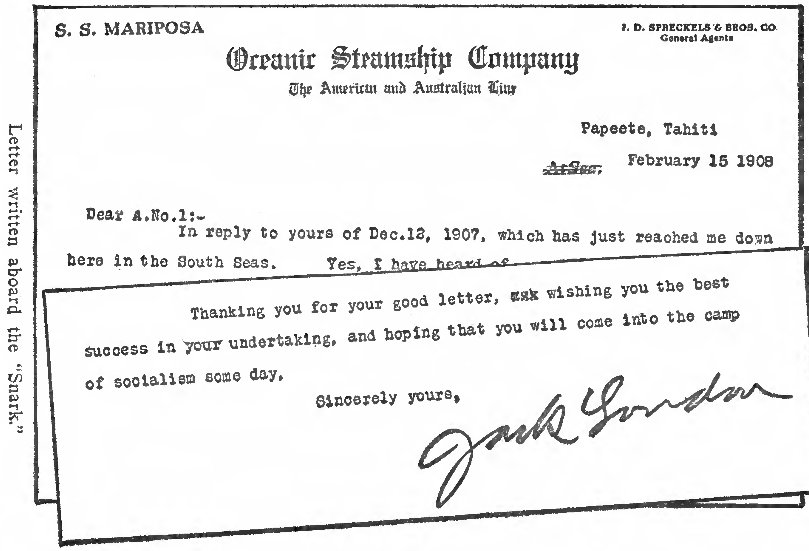

Among no end of other most worthy services performed by the memorandum, many an envious “knocker” had his blatant mouth shut up in short order by a perusal of its pages. It contained records which irrefutably proved that I, who was a homeless outcast, had gloriously made good where all my fellows had failed to gain even a fleeting remembrance by posterity. There were recommendations galore donated by grateful railroad companies and others by individual railroaders for saving—ofttimes at the risk of serious personal injury—trains from wreck and disaster by giving timely warning of faulty condition of car or track equipment. And letters penned by appreciative parents of youths, and others by some of the waywards themselves whom by the thousands I had induced to forsake an unnatural existence which was the straight path to mental, moral and physical perdition. And newspaper clippings by the score which mentioned deeds worth while I had performed—in many instances years prior to the time publicity was accorded them. And autographic commendations by a long line of national notables, such as Burbank, Edison, Admiral Dewey, three of the presidents of the United States, a governor general of Canada and others too many to enumerate in limited space.

By reason of this record and the fact that I was a total abstainer—which was a case of utmost rarity with the hoboes—I was regarded by newspaperdom as an authority concerning everything pertaining to the Road and the tramp problem in general. Therefore my loud-spoken remark to the reporter that there were abroad in every community folks who would blindly accompany a hobo, elicited the retort by Editor Godwin which was chronicled at the opening of this chapter.

“How will you prove your contention, A. No. 1?” Mr. Godwin inquired when I had reiterated my assertion.

“Allow me sufficient space in the ‘Help Wanted’ columns of your daily for the insertion of an announcement asking a traveling companion for a hobo, sir!” I returned, assured that my demand would be refused point blank.

Contrary to my expectation, Editor Godwin considered my suggestion. Making use of his desk telephone, he held a consultation with the management of the newspaper’s advertising bureau. The conference resulted in the granting of my request.

In the morning issue of the World this advertisement made its appearance:

Wanted—travelmate by hobo contemplating roughing trip to California. Address: Quick-Getaway, Letter Box, N. T. World.

The afternoon mails brought a veritable avalanche of responses. Other dozens of letters were delivered by special messengers. Several telegrams arrived, some of which had prepaid replies. All had come from correspondents who had most greedily snapped up the tempting bait of the phoney advertisement

The messages originated from all walks of life and were of every kind of offer and demand. Inquisitive inquiries predominated, as a matter of course. Again, many of the answers were dictated in a jocular or sarcastic vein. Some of the replies were of such a memorable character that I recall them to this late day.

One came from a patriarch who stated, that, though he had six married sons, he had all his days nursed a strange fascination for the outdoor life, that to satisfy this great craving of his he would gladly consider an acceptance of the position. Wishing to convey a literal estimate of his personal prowess, he frankly wrote: “Although I am right smart up in years, I still am as spry as a bad wildcat!”

Another letter of this class was forwarded by a brokenhearted mother. The unfortunate lady pleaded that her son, a reprobate, be taken away from the city as an only means of saving his unfortunate family further shame, if not disgrace far worse.

“Haven’t I correctly judged the degree of ignorance manifested by the average citizen when it comes to a lucid idea of what the Road really is, Mr. Editor!” I cried triumphantly, when on wearying of opening the letters, which still came pouring in, we consigned the remainder of them to a waste paper basket.

“The material you have provided we shall work up into a story that will be warning long to be remembered by every soul who answered the advertisement, A. No. 1!” Mr. Godwin declared, at the time I took a final leave of him and his editorial staff.

In the morning, and ere I quit the city for another destination, I called at the letter box to pick up mail which might have arrived during the preceding night. While I scanned the contents of letters handed me by the clerk in charge of the mailing division, I was tapped lightly on the shoulder by some one who desired to attract my attention.

“Pardon my interrupting you, sir!” a stranger said, excusing himself. “But as I noted by the address of your correspondence that you were the Mr. Quick-Getaway who has advertised for a traveling companion, I dared to accost you to request a personal interview.”

The speaker was a youth of perhaps eighteen years. His five foot seven of stature, though of rather slim proportions, displayed every indication of holding no end of latent animal energy. A mass of rich brown hair tumbled well down on his forehead, shading a pair of gray eyes which gazed at you, keen and penetrating. At the moment they were a-smile—this no doubt due to the immense satisfaction it brought their owner to know he had stolen a march on his competitors for the hobo job which was so greatly coveted.

This was his wearing apparel. A traveling cap which he wore jauntily tilted to the side of his head, and a navy-blue flannel shirt with collar attached. He had no vest. His coat and trousers were much the worse for rough usage. A pair of brogans of a medium weight completed the outfit.

Courteously lifting his cap, the chap went on: “When are you to depart from the city, sir?”

“Is that any of your concern,” I sharply let hint know, taken aback by the fellow who had caught me off my guard, also believing that my intentions were none of his business.

“As I, too, am ready to shake this burg for California, I am willing to stake you to my company!” he continued unawed by the reproof, faithfully acting the role of the dog who adopted his master.

“And who, then, are you?” I flared, aroused by his impertinence.

“I’m out looking for a comrade with whom to hobo-cruise around the globe, friend!” he replied, revealing his plan.

“Then you’re on the wrong tack for I am no sailor!” I informed the persistent fellow, temporizing with him for the sake of not drawing public notice to our unfriendly conversation.

“That’s why I believed it to be most desirable that we travel in comradeship to the Pacific Coast, pal,” he came back undismayed. “There I belong in Oakland, across the bay from the city of San Francisco, where I want to stop a while to visit with my folks prior to continuing my jaunt by sea.”

I was at the point of treating the stranger to a tart rebuff, when that wagging tongue of his resumed: “You’ll find me to be reliable and strictly on the square. Should I turn out disappointing, ditch me en route anywhere you prefer. And, should we get along together, what’s the matter with doubling up for the rest of the trip I have in view. I’ve been a sailor and know how to make things pull easiest aboard ships. It always was my pet project to make a journey around the whole of Mother Earth. As I’m determined right now to make a start-off on such a rove, wouldn’t you like to come along?”

Thus the youth prattled on. Running counter to the great dislike I had fostered against his person and personality, ere I was aware of this change, I had acquired a deep interest in the speaker because of his odd proposition. Too, there was an honest sound closely bordering on outright bluntness ringing through his appeal. All this combined to send my thoughts running riot.

All my days I had yearned to see the world by way of a circling trip. Only too well I recalled characteristic incidents of my school days. Then countless times I was reproved by the teachers for sitting with eyelids held widely open but with eyes entirely oblivious to surroundings. For I was allowing daylight dreams to drag me away to far-off shores and on and ever onward seeking hair-raising adventures among strange peoples—until the harsh words of my enraged preceptors rudely tore me from the willful neglect of my lessons. (No wonder then, that I did not shine at school! At thirty-eight sheer necessity compelled my commencing the study of books of primary education.)

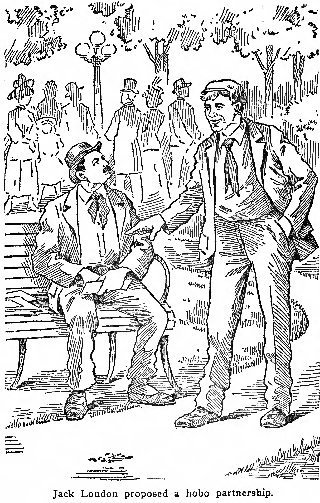

While these lively thought-bees busily buzzed through my mind, thus arousing to a more furious flare the wanderlust which already held me enthralled, I hearkened to the invitation of my tempter. By the time he had concluded, I was on edge to have a further investigation of his prospects. I proposed that we adjourn from the crowded business lobby of the World to a bench I chanced to espy as standing vacant in the nearby City Hall Park—a bit of breathing space in the heart of a group of towering skyscrapers.

“And what might be your name, sir?” I asked the youth when we had occupied the bench.

“It’s Jack London, sir!” he simply stated, then an ugly scowl came on his countenance for I had broken into a merry laugh while I explained that I had asked to hear his correct family name and not his moniker.*

“That’s what it is! Exactly as you see it spelled out in the address of the envelope of this letter I received a couple days ago here at the General Delivery!” he remonstrated, as if he regarded my comment as a personal affront.

“I understand! You purposely transposed your road-name to have lawful passage in the government mails accorded to your correspondence, sir!” I replied when I had read the address of the letter. Then quite assured that I had struck the key of the riddle, I continued, “After all, your moniker is ‘London Jack’ meaning that you are a tramp whose call name is ‘Jack’ and who originally hailed from Old London Town or other community which adopted this name as its own.”

“I was tramp-named ‘Cigaret’ and ‘Sailor Jack’ by fellows with whom I’ve roughed it on land and water, but ‘London’ is my correct family name!” he insisted.

“Whichever moniker you prefer, ‘Jack London,’ ‘London Jack’ or any other which strikes your fancy, what are your plans?” I impatiently quizzed, aiming to get a straight conversation under headway.

“Today I am going to leave overland. This will be the first stretch of a journey comprising a mileage of no less than twenty-five thousand!” he briefly announced.

Seeking information on a very important matter, I asked: “And how are you fixed financially?”

’This forenoon I spent my last cent on a postal card to advise my folks that I am about to pay them a brief call,” he admitted.

“Then we are both in the same unfortunate fix, my boy!” I groaned commiseratingly.

“Yet you had the nerve to insert that tantalizing offer!” he came back in sharp reprimand.

This retort caused me to account for the events which preceded the insertion of the advertisement. I explained how for my meals I had stood off Editor Godwin. That at night I had flopped a-top a battery of boilers connected with a power plant which was placed in the lowest of the basements which in the World Building extended three-deep below the street level of the metropolis.

Mutual confessions were in order. From one stage of quick acquaintance we drifted to another. He feelingly spoke of his past. He mentioned incidents which had occurred in the days of his childhood when he was a member of the family of a poor ranchman. He told something of his experiences as newsboy, factory hand, cannery laborer, oyster pirate and of his connection with the fish patrol which policed the waters of the Bay of San Francisco and the estuaries of the Sacramento and the San Joaquin Rivers. He bitterly complained that so relentlessly had he been driven to his tasks by his workmasters, that, step by step, his belief in receiving a fair-deal by his fellow-men was undermined. Then he had abandoned himself to the Road—the abyss, figuratively, which among other human scum, engulfed the derelicts produced by our intense civilization.

“There seems to be nothing to prevent our becoming hobo comrades and, I hope soon, the best of chums, fellow!” he said, reiterating his original plea when he had concluded the review of his personal history.

“But I am bound for Boston and the scenic section lying to the north of that city!” I informed him, stating the route I intended roving.

“It’s a most simple matter for a tramp to change his travel plans to suit the occasion!” he quickly countered. “By doubling up with me, you too, maybe, will make my globe-trot!”

Thus irresistibly ran the line of his argument. He decisively checkmated every objection I dared to advance. In no time I found myself outgeneraled on every point I tried to score against a partnership. Finally, he who was my junior by four years compelled my consenting to become “his” travel mate for the term of the circle trip of the globe, which he was contemplating.

The dry advertisement which in a spirit of rank bravado I had caused to be inserted in the newspaper had come home to roost in the shape of a boomerang. I, who had derisively snickered while perusing the correspondence of more than five hundred fools who had yearned to become a companion to a hobo, had myself fallen an easy prey to the self-same lure. A hobo comradeship resulted which culminated in a friendship which firmly endured until the death of Jack London.

* Spoken: mo’nee’ker—the nickname every hobo assumed.

“The Smoky Trail”

Having arrived at an understanding on the matter of partnership, we allowed our conversation to become a conference, the object of which was the selection of a railroad route whereby to reach the Pacific Slope.

In eighteen hundred and ninety-four there were nine distinct railway systems running westward from New York City. To the uninitiated these railroads looked as much alike as an equal number of beans in a pod—to cite a familiar comparison. But to the professional hobo there were no end of fine distinctions to be discerned which had carefully to be considered before he decided on the line over which he “hit the Smoky Trail.”

Some of the nine railroads, while maintaining a faultless passenger service, had woefully neglected or “red taped” their freight traffic. One of the larger of the systems actually penalized engineers who dragged freight trains over its splendid trackage at a greater rate than ten miles an hour. Another of the railroads had deliberately permitted that portion of its business which was transported in “varnished” cars to deteriorate to such a degree of slovenliness, that this service became the butt of common ridicule. On the other hand, this rail line maintained a cargo service which was so expeditious that shippers most liberally patronized this, its only modernized department. Then there were roads which though otherwise considered as “free and easy” by the wanderlusting fraternity, served communities—sometimes lone water tank stops—where officers of the peace raised havoc with the “liberties” of the tramps. Again, there were the “hunger lanes,” thus nicknamed by the Wandering Willies because they passed through territory the populace of which either was “strictly hostile” or refused to “produce” in response to further “battering” for alms.

But of an almost invaluable importance to the devotee of vagabondage was the exact knowledge of the location of the lairs of the railroad “bulls.” At that time (1894) the railroad officers had just commenced to transform the idyllic existence of John Tramp into an interminable living nightmare which was filled to overflowing with drubbings, clubbings, long terms in workhouses and, worst penalty of all, self-supporting prison farms, the “key” of which was thrown away until the time the hobo had absolutely reformed.

(I first hit the Smoky Trail in 1883. Then the railroads comprised 190,000 miles of trackage and 25 just about covered the number of effective detectives employed by the transportation companies. By 1894 the membership of the railroad-salaried sleuths had mounted to 275. At present (1917) 7,410 special officers are required to police a mileage of 257,570. These statistics not only prove the phenomenal increase in the criminality of the hoboes but also the lack of common sense in human beings who will cheerfully stake their life and liberty against odds so utterly hopeless.)

For some time prior to our meeting, Jack London had lived the life of the Road. He had negotiated one complete transcontinental round trip. At this moment he was about to start on the return journey of a second hobo jaunt. But neither his scope of railroad knowledge nor the vast practical and otherwise experience, which I had acquired during the more than a half of a score of years which I had roughed it, was to be of any benefit when we came to select a route of traveling from New York City. We found ourselves effectively shelved by the simple circumstance that neither of us commanded the six cents which was necessary for our ferriage across the Hudson River to Hoboken or Weehawken or Jersey City where eight of the nine westbound railroads had their termini.

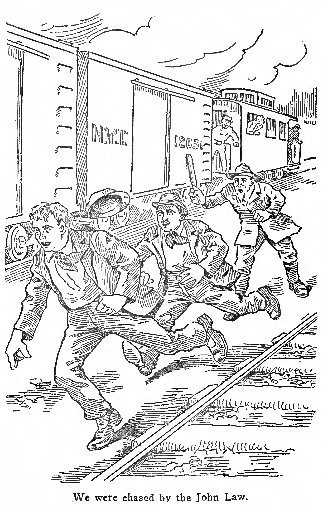

This left us the New York Central Lines as an only avenue of exit from New York City. Quitting the park bench, we walked to the Grand Central Terminal, which railroad station was located in the heart of the metropolitan business district. We had rashly calculated that it would prove child’s play to slip, mingled with a crowd of bonafide railroad patrons, through the depot to where we could board an outgoing passenger train. Arriving at the gates, the only available entrance to the train shed, we staged any number of futile attempts to run the gauntlet of ticket inspectors and other guards. The disturbance we created was such that somebody tipped us off to the police. Forthwith we found ourselves “pinched” by a John Law who, kindly fellow that he was, confronted us with the alternative of instantly quitting the railroad premises or serving a stiff term at Blackwell’s Island, the penal colony of the municipality. We readily chose the lesser of the two evils and went our way without waiting for further unpleasant developments to ensue.

Having had our initial start thoroughly queered, we set out on Lexington Avenue to reach the New York Central freight yard which then was located at One Hundred and Fifty-Second Street. While we plodded along the seemingly endless avenue, now and again we stopped en route at private residences and shops to panhandle food. Everywhere we “battered” we were tartly sent on our way. Evidently consecutive generations of professional mendicants and others had exhausted the charity of the New Yorkers we tackled for donations. Dusk had begun to blend with darkness and we were but a short step from our destination, when Jack London managed somehow to secure a loaf of stale bread at a baker’s.

“Let’s camp on the curb of the street and have a royal feast, pal!” he jubilantly cried on returning to where I was waiting, triumphantly holding aloft the precious gift.

“And attract the attention of the mounted police!” I frowned, giving a warning which made him quite willing to continue our walk.

Beyond the further end of the freight yard and near the switch by which the outlet siding connected with the main line of the New York Central, we found a resting place upon some discarded railroad sills (ties). Scarcely had we seated ourselves, than below us in the yard we heard shooting and wild shouting. Shortly afterward a man rushed by where we were lounging. Seeing us and correctly surmising why we were near the spot where trains departed from the yard, he called out that sleuths were at his heels. Another instant—and carrying the loaf of stale punk, we, too, had joined in the headlong getaway. We were running in the race betwixt the fugitive and the John Laws from whom we managed to escape after they had chased us quite a distance.

The fellow who had saved us from the penalty of the law was a hobo. He introduced himself as “Stiffy Brandon.” His moniker indicated that for a beggar craft he had chosen the one which imposed upon the credulous by stimulating the awful affliction of the paralytic. He told how he was scared up by special agents and had run for freedom while bullets came mighty nigh whistling his requiem.

In the company of Stiffy Brandon we continued on the track until we reached a “tower.” In the days prior to the installation of automatic train protection, a two-storied structure held a telegraph operator who from his vantage point in the second loft of the tower guarded the passing traffic against collisions and other disasters by signalling to the train crews by means of colored flags and after nightfall with lamps of various colors.

Whenever trains approached each other too closely for safe railroading, the towerman brought the offending crews to terms either by reducing the speed of or halting their trains. It was to wait for a chance of the latter sort to hobo onward that in a thicket located but a short distance from the track and tower we lighted a low-burning smudge the warm glow of which afforded protection from the night air and the thick fog which heavily shrouded the valley of the Hudson.

“Do you wish to share the bread with us, stranger?” kindly inquired Jack London when we were ready to make away with the loaf.

“Since early morning I haven’t touched food, friends!” the fellow admitted, accepting our charity.

“It’s like casting bread upon the waters!” laughed Jack London while he handed a third of the loaf to Stiffy Brandon who joined us in bolting the pittance of food.

When we had lunched we improvised pillows by rolling our shoes into our coats—a common usage practiced by tramps. Then we stretched ourselves by the side of the campfire to take a rest while we waited for a train to stop.

Jack London awakened me from the deep slumber into which I had sunk wearied by our long march, a distance of more than two hundred paved city blocks. On the main line and almost abreast of where we were camping, stood a passenger train, halted by the towerman and awaiting his signal to proceed on its journey.

“Where’s the other guy, Jack?” I asked rubbing the sleep from my eyes, noticing the absence of our fellow-tramp.

“And where are our coats and shoes?” stormed my travel mate, calling attention to the fact that our pillows, too, had disappeared.

“The scoundrel with whom we broke bread, has done us this turn to prove his gratitude!” I angrily shouted.

But we promptly realized the full extent of our predicament. I proposed that we take advantage of the moment by hoboing the passenger train to a town or city where the outlook would be more promising to panhandle other coats and shoes than it was at the lone watch tower by the railroad.

In our stocking feet we painfully stumbled to the side of the track. We arrived in the nick of time to swing aboard the departing train onto its “blind baggage,” as is called the front platform of the first car coupled to the rear of the engine tender.

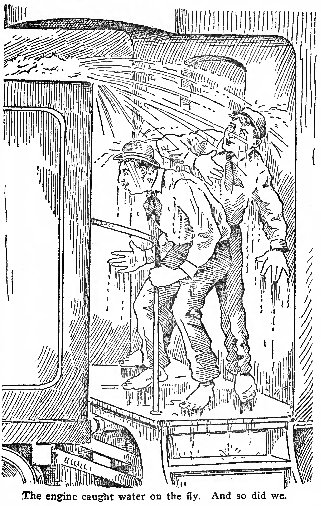

While we were discussing the miserable treatment we had received at the hands of a hobo we had trusted to be incapable of robbing his own kind, the train, then running at a fair rate of speed, began to take water from a track tank. This was a chute-like contraption a quarter of a mile in length, made of flush-riveted plates and built between the rails in the center of the track. From an adjacent pumping station water was let into the chute from where it was drawn aboard the moving train by means of a scoop which extended at an easy gradient through the bottom plates of the engine tender.

“Hustle over here, A. No. 1! See our train taking water on the fly!” Jack London cried out in excitement, bringing me hurrying to his side where between the cars we could watch the process of the track tank.

Neither of us had previously hoboed the blind baggage of a passenger train of one of the few railroad systems which at that time were equipped with track tanks. Furthermore, we were quite innocent of knowledge of the fact that the water chute held a capacity to supply the requirements of the wet fluid to “double header” trains, as trains pulled by two engines were called in the parlance of the railroaders.

Soon the capacity of the tender of our engine was reached. Then the surplus shot over the rear of the tender. This overflow caught us on our necks as we were bending over to watch the sight. The water struck us with the enormous pressure produced by the immense force of the speeding train on the water drawn upwards in the scoop. But for the fortunate circumstance that to gaze downward the better, we had taken a firm hold of the guard railing of the platform, for a certainty we would have shared the fate of the many trespassers who were washed off moving trains by the overflow from track tanks to be dashed upon the right of way and there to meet a most horrible death.

As it was, we were almost drowned in the torrent of the overflow. When we had traveled beyond the zone of immediate danger, wet through and through as we were, we were chilled by the cold draught of air generated by the train which soon after leaving the track tank attained a speed of better than a mile a minute.

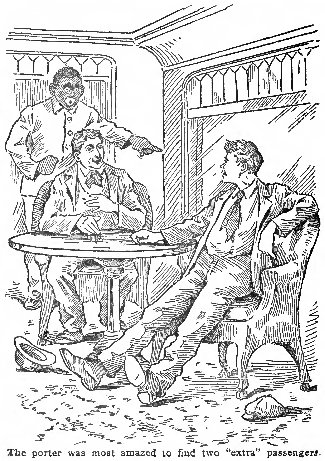

Seventy miles further on, at Poughkeepsie, the train made its first halt. Even before the coaches had been brought to a complete stop, we were taken in charge by a railroad sleuth. I could readily recognize our captor to this day, as then but recently a savage hobo had bit off one of his ears. The officer marched us to the city lockup where the warden, Samaritan that he was, supplied us shivering ones with shoes from a collection of castoffs brought to headquarters by the local police. While most charitably inclined, our friend proved himself very remiss in the performance of his official duties, or, and this was most likely, he had intentionally left improperly fastened the door of the cage into which he had placed us. Anyhow, when on an errand, he went from the calaboose, we released ourselves from the cell and left the jail. Then we hurried from the city by way of alleys and byways which were not frequented during the hush of the night.

“In the Thick of the Hobo Game.”

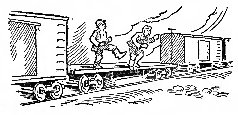

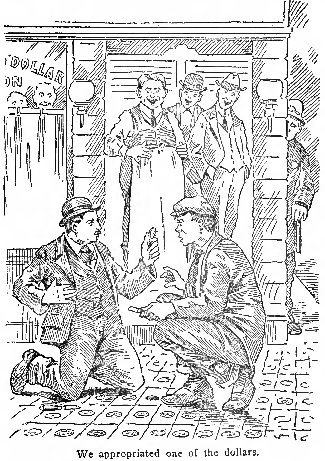

Break of day was painting the eastern horizon with rainbow tints, when we swung aboard a freight train passing at reduced speed through Rhinecliff. Unmolested we hoboed to the West Albany Yard where a policeman went for us. By a very close shave we escaped arrest. Later on we climbed aboard an outtlound train of empty stock cars. We had scarcely entered a car, when coming in by an end door, a brakeman paid us a visit.

“Got any money on which to ride, fellows?” he roughly asked. At the same time he threateningly whirled a stout hickory club, such as was carried in the days preceding the universal introduction of automatic brake devices by every trainman for use in setting and releasing of the brakes.

“We are down-and-outers hunting for employment, sir!” Jack London humbly volunteered, excusing our presence.

“Do you carry cards?” gruffly inquired the railroad man, having reference to identification cards issued to members by labor unions.

“We’re non-unionists, friend!” admitted my hobo mate, finding himself cornered.

“Scabs shan’t ride my train! Therefore, if you fellows value your hides don’t allow me to catch sight of you aboard these cars after this train quits the Schenectady water plug!” he roared at us and then withdrew from the car.

In the stock car adjoining the one we were hoboing, the shack found other trespassers.

Presently we heard him snarl: “Got any money with which to square yourselves for this trip?”

The answer he received must have proven an unsatisfactory one for presently he called for a showdown of union cards.

“Here they are for your inspection. They are paid to date, Brother Workman!” was the reply which echoed above the racket raised by the cars.

“Where’re you boes traveling to anyhow?” growled the brakeman.

“To Rochester where we’ve got jobs waiting our arrival, friend!” he was told.

“There are already too many men out of work now at Rochester! Therefore, if you fellows value your hides don’t allow me to catch sight of you aboard these cars after this train quits the Schenectady water plug!” warned the railroad shack who grafted while his job lasted. Then he would appear, sailing under another assumed name, on some other railroad where he plied his crooked game until frowned upon by his honest fellow-employes who usually lent a helping hand to have the unprincipled “boomer” discharged from the service.

Among the tramps who were left behind at a water station located some miles beyond the city of Schenectady, we discovered Stiffy Brandon, the rascal who so meanly had repaid our charity. He grudgingly confessed that after he robbed us while we were sleeping, he had sneaked back into the freight yard.

There foolhardily defying arrest, he had come away from New York aboard the same freight train with which we had connected at West Albany. He already had disposed of the footwear. But he wore our coats drawn over his own, one squeezed into the other—this in accordance with a custom observed by all hoboes who were seeking purchasers for garments dishonestly obtained. We took charge of our coats. Then we settled for the theft and the absence of our shoes by handing the scoundrel such a sound drubbing, that when we chased him from the vicinity of the water plug, he swore to even the trouncing though this necessitated his following us all the way across the continent.

Soon afterward a train pulled up to take on water. We crawled into a hiding place aboard. With the exception of a close race with a city cop who at Utica hot-footed it after us, we had no other encounter worth while chronicling until we landed in the western outskirts of the city of Buffalo.

“Hyenas in Human Form.”

The freight yards of the New York Central Lines were located at West Seneca. In close proximity to the extensive terminal were the residences of some of the employees of the Buffalo street car system. During the day many of these men rang up fares, twisted brakes and controllers and honorably earned stipends considered quite sufficient to meet the needs of fellow-workers who were not let in on the graft the others plied after nightfall. Then they hooked to the coats of their uniforms a badge supplied to its constables by Erie County, New York. Equipped with club and revolver they set out on a hunting expedition. Odd indeed was the quarry stalked by these gents in the dark when Br’er Rabbit and other prey of the legitimate huntsman had retreated to their lairs. The street car roughs were hunting penniless out-of-works who, in many instances, had dependents looking to them for support. Fortunates who had daily bread a-plenty were searching for unfortunates who not even had a place to rest their weary bodies!

Judas Iscariot who for paltry shekels peddled his immortality stood no comparison with the black souls of these residents of Buffalo. The miserables which they caught were handed over to the authorities for a fee amounting to twenty-five cents for each prisoner. The law sent the unfortunates to serve long terms in the Erie County Penitentiary, then universally conceded to be the most shameless money leeching proposition within the confines of the graft-ridden state of New York.

As were all hoboes who had attained or were aspiring to attain the professional rating, so Jack London and I were amply apprised of the great menace which threatened every box car tourist who dared to linger after dusk at West Seneca yard. Furthermore, only recently while hoboing eastward, Jack London was “glummed” at Niagara Falls, also in Erie County, where he drew down a sentence of thirty days which he served in the notorious work-house.

It was night time when we arrived at West Seneca. Without tarrying an unnecessary moment we continued westward on the track until we walked into Angola. In the morning a freight stopped at this first water stop beyond Buffalo. While looking over the train for a likely hiding place, we ran across a stock car loaded with cabbage. An end door of the car stood ajar—possibly somebody had helped himself to a mess of the succulent vegetable. We climbed aboard the car and barricaded the end door with cabbage heads. Then we built for ourselves from the green goods a nest the sides of which reached almost flush with the ceiling of the stock car. From our hiding place we could peek about but were protected from casual observation.

Coupled ahead of the cabbage car ran a gondola loaded with heavy machinery. When the train began to draw away from Angola, a fellow swung aboard this car. A moment after he had concealed himself in the machinery, two other men boarded the gondola. That they were dangerous scoundrels they proved when the freight had attained a high rate of speed. They made the hobo crawl from his hiding place and had him hold his hands aloft while they searched through his pockets. They found nothing worth taking away. Just the same the inhuman hounds forced the poor fellow to leap for his life from the racing train. Man was not built to hop from speeding cars to rock-ballasted track where there awaited him death or lifelong crippling. On a grade several miles beyond the scene of their beastial deed, the robbers quit the train.

While the yeggs had no inkling that we had witnessed their crime, an alert brakeman who chanced to stray over the top of the cars, spotted our roost. He saw to it that we had a stop-over at the next halt of the train. This was Erie, the hustling lake port city of Pennsylvania.

To avoid running counter of yeggs, we decided to ride passenger trains until we had passed Cleveland. Then the Buffalo — Cleveland district of the railroad was the stamping ground of numerous bands of hobo cutthroats who preferably preyed upon fellow-tramps.

From Erie we made the “White Mail.” Climbing on behind us onto the blind baggage of the crack train came two youths who acted so awkward on the job, that a third trespasser, an elderly, typical hobo, lent them a helping hand while they mounted to the platform. Even before the train had drawn beyond the limit of the Erie yard, from snatches we caught of a conversation into which the trio had entered, we became informed that the nasty tramp had induced the lads to run away from their homes. He promised to guide them to Texas where they would lead the life of cowboys. He proposed other crack-brained inducements for the youths to embark upon the lawless and degenerate existence of the wandering beggars of hobodom.

“Do you recall the turn which the ‘stickups’ today handed to the poor bum?” Jack London remarked in a mumbled aside, not wishing that the others overhear his comment.

“What has that got to do with these chaps?” I perplexedly retorted, not noting a connection.

“Abide your time and you will learn!” he rejoined and then we returned to listen to the lofty air castles which were rated as truths by the guileless boys who with all-absorbing interest hearkened to their tempter.

At Conneaut, Ohio, a freight train blocked the progress of the mail. Our train halted while the freight cleared the main line by backing over a crossover switch onto the eastbound track. Then the “Fast Mail” preceded on its journey. The train had attained quite a bit of speed, yet was running none too swift to serve his purpose, when Jack London called the attention of everybody to something which seemed to have occurred on the track at the side of the train. A first view was allowed to the burly tramp who had eagerly pressed forward. The fellow had leaned far out from the car and was lightly balancing himself with the tips of his toes upon the rim of the platform when Jack London gave him a sudden shove which sent the detestable vagrant spinning into space.

“He’s merely cashing in less, by far, than that which by rights he so richly deserved for attempting to ruin your chances in life, lads!” my comrade told the waywards when he finally managed to reassure them that we were their friends and not hobo yeggs.

Quickly the train attained topnotch speed. Evidently, the engineer was driving his engine at fastest rate while endeavoring to retrieve time lost by the delay. While the cars raced onward, in the narrow limits of the coach platform was enacted one of the strangest episodes I encountered in the course of my world -wide wanderings. Jack London, himself a wayward youth, undertook to preach to the runaways the truth that the worst of parents was a veritable saint in comparison with the best guardian the abyss of hobodom had to offer. It was a matter of two hours ere the express reduced its terrific pace on entering the yard at Collinwood, located a short distance east of the limits of the city of Cleveland. All the while my hobo mate bravely continued his preaching until over and over again the lads had promised that they would return home by the first train.

As the “White Mail” rolled under the train shed of the Union Station at Cleveland, we dropped from the blind baggage to the ground. Detectives routed us. So anxious did the sleuths seem to lay their hands on our persons, that, maybe they had received telegraphic orders for our apprehension. Possibly the hobo who was bounced by Jack London at the Conneaut crossover was injured by his fall. Society will slobber over and tenderly care for every hobo who receives a deserved bump. But how many citizens are there who would waste the least attention on a professional beggar who, frequently posing as a workingman, nowadays might often be seen hoboing over the land with from one to a dozen minors whose futures were invariably and irretrievably blasted by the criminal of criminals who stopped short of nothing.

In the heat of making our getaway the waywards became separated from our company. And this is my fervent hope: that they and theirs practice toward others the service rendered unto them by noble Jack London,

“The Hoboes’ Pendulum of Death,”

This day we caught a fleeting glimpse of Stiffy Brandon! Having accomplished a clean getaway from the officers, we thoughtfully accorded a wide berth to the premises of the Union Station. We regained the railroad a safe distance from the zone wherein for us lurked trouble. While we walked on the grade which steeply rose from the banks of the Cuyahoga Creek, the pride of the Clevelanders, a passenger train overtook us. As the cars flashed abreast of where we stood on the right of way, we saw a hobo dangling from the gunnels—these were the inch-gauged trusses which helped to sustain the weight of the coach bodies. We recognized the rod-rider, though he failed to see us as he held his eyes tightly shut against dust and cinders which whirled about in the draught created by the train. We highly appreciated the fact that the fellow was unaware he had out-hoboed us. Every hobo, including the slovenliest, firmly believed himself to be the wisest of the wise and to stand without compeer in the fraternity.

In other respects this was our day of misfortune. Near the summit of the grade we boarded a passing freight train. While the train stopped at Port Clinton, we went to a residence located nearby to ask for a drink of water wherewith to quench our thirst. Repeated ringing of the door bell at the front entrance brought no response. Then we tackled the side door with no better result. And though we knocked for some time at the kitchen entrance none came to attend to our want. Deciding that no one was at home, we helped ourselves to our needs at a pump we espied in the back yard. Then we retraced our way to the tracks. There, while we patiently waited for the train to resume its journey, we were nabbed by a constable.

“I want you fellows on a charge of being dangerous and suspicious characters!” snarled the John Law when we vehemently protested against the outrage.

But he took no stock whatever in our objections; quite to the contrary, he came back by snapping handcuffs to our wrists. Then he conveyed us to the residence where we had drunk our fill of water. A typical old maid met us at the entrance of the house.

“For sure! They are the lads who tried to burglarize my home, Mr. Officer!” cackled the ancient dame, identifying us. “They attempted to enter here by way of the doors. Failing to gain an entrance, they were wrenching off the handle of yonder yard pump, when they were chased away by the barking of Atkinson’s dog.”

Explanations were in order. We had almost exhausted our vocabulary for words wherewith to plead our innocence of intentional wrong-doing, when the constable, though most reluctantly, permitted our release from custody.

At this juncture, the freight train began to depart from Port Clinton. An empty box car with its doors standing ajar most invitingly beckoned for a continuance of our journey. Posthaste we ran to connect with the open car. But the minion of law and order took after us. Most likely, he saw a chance to work up against us a “case” which could be made to “stick” in court. Fee-hungry as he was, he ran so close at our heels, that we escaped from his clutches only by a headlong dive from the car by the door which stood open opposite to the one by which we had entered and through which the cop had climbed aboard to capture us. We hurriedly mounted a side ladder of a passing freight car. But to the roofs of the cars went the John Law chasing us and so compelled our return to solid ground. There he raced after us alongside the moving train. We were pressed so closely by him, that as a last recourse, we swung onto the gunnels beneath a freight car. Fearing the risk of injury, the cop refused to dive under the running car. He contented himself to trot by the side of our traveling haven of refuge, all the while bawling commands demanding our voluntary surrender.

“Never count your fees until you’ve got them earned!” derisively sang out Jack London, at the moment when the constable abandoned the foot race with the train which was running at an ever faster rate of speed.

Onward we traveled lazily stretched across the gunnels and enjoying a deserved respite from the strenuous man-hunt we had sustained. Quite ignorant of the fact that the members of the train crew had witnessed the fray, we entertained each other with joshing at the expense of the officer whose authority we had put to naught. But the crew, the rulers of the train, were law-fearing folk who doubtlessly looked askance at our wanton defiance of mandates by which they, the railroaders, abided. The first thing we were to be aware of, we who were riding in the cellar of Hades beneath the jolting car, was to behold how a member of the train crew left the caboose which swung at the tail end of the train and came running forward over the roofs of the cars.

Although we could not see the man who was abroad beyond the constricted arc of our range of vision, we had a means which allowed a close tab on his doings. This merely was a matter of keeping a watch on his shadow to be conectly informed of his designs and whereabouts. The silhouette of any trainman abroad on the cars while under way was cast groundward by the sun or, if after nightfall, by the moon, or should the night be a moonless or overcast one, then by the rays emitted by the lighted lantern which after dusk was carried by every railroad man employed on trains or trackage.

And this day the sun shone from a cloudless sky. The shadow of the railroader informed us that he was coming forward and that he had abruptly stopped on arriving a-top of the box car beneath which we had taken lawless passage. He was a brakeman as this fact was borne out by the hickory brake club he carried. He descended on a side ladder of our freight car. Arriving at the lowest rung of the ladder, he took a survey of the lower works of the car and only when he had assured himself that he had correctly judged the distance from the caboose to our hiding place, he yelled: “The conductor of this train has ordered that you get out from under this train. Right now! Instantly! Do you hoboes understand!”

“Get us out from under this speeding train, if you can, sir!” the brakeman was dared by Jack London who was cocky from having defeated the designs of the Port Clinton police officer.

The railroader neither heeded London’s tart invitation nor uttered a syllable in reply. But almost instantly the color of his countenance turned to a livid crimson—a telltale sign of fury otherwise controlled. Presently a diabolic grin made an appearance in his face. To us who believed ourselves safely ensconced beneath the car, this hard grin only helped to confirm our belief that no common agency could dislodge us from under the train—at least not while the cars continued to race at better than forty miles an hour.

Having received our defy, the brakeman climbed back to the roof of the car. We heartily laughed when we saw by his shadow that he was returning to the caboose. There he remained but a brief while, for presently we noted his coming again forward over the cars. But this time he carried a coil of light rope—judging the gauge by the diameter of its shadow. On his approaching to where we were, we discerned a coupling link dangling from one end of the rope. The link, weighty and made of wrought iron, was of the pattern used in the days prior to the universal introduction of automatic car coupling devices.

As the railroader had done on his preceding trip, so at this instance, he halted when he had arrived on the roof of our car. We broke into boisterous laughter at the remarks of derision which we passed regarding the helplessness of the shack in the face of our determination to hobo his train in spite of his orders to the contrary. But the very next minute our laughter was superseded by groans. By merest chance, I glanced at Jack London. His countenance had assumed an ashen-gray overcast. His eyes were protruding. Further, I could hear his teeth clattering too. I felt myself shuddering. And there were no end of other mental and physical manifestations to prove that we both were suffering in the agonies of mortal fright.

There was ample occasion for our panic. The shadow play had told how the trainman had uncoiled the rope. Then he had deliberately lowered the coupling link into the canyon formed by the front wall of our car and the rear side of the one coupled ahead.

A faint metallic clinking was heard. It emanated from the heavy link coming in touch with the coupling apparatus of the cars. On our part another throe of most dreadful fright—then Rip! Crash! Thump! Smash! came thunder-like detonations due to the contact with the stationary track by the coupling link which sustained the momentum of the racing cars. These detonations alternated with crunching, crushing and splintering which resounded from the havoc wrought to the iron and wood work of the car by the heavy link which was propelled by titanic force to and from the track, thus faithfully copying the motion of a gigantic pendulum wrecking destruction to everything coming within the radius of its swing.

As the brakeman gradually paid out the rope which held the iron weight in check and to its work, at a similar ratio our personal danger increased. Nearer and ever nearer approached the hideous weapon to where we lay huddled against the gunnels’ cast iron supports which transverse limited our retreat from the path of the tool of vengeance employed in bygone days by irate railroaders.

I lay farthest from the death-dealing railroad iron. That is, if the width of a human body might be reckoned to be a span worthy of measurement. But on this occasion even this negligible distance made a vast difference in our demeanor confronted as we were by death. Protected by the body of Jack London from the thick shower of debris, I instantly realized our dire peril. I yelled to London to hurl himself from the moving train irrespective of the consequences of such a leap to the stationary right of way. He neither made a least move nor offered a reply but dazedly stared at the ricochetting link—in fact, he was rendered inanimate by terror of the horrible fate which threatened us.

The paying out of the rope had allowed the link to come within a few inches of where Jack London lay helplessly paralyzed with fear. It was then that I collared my mate by his coat, bodily dragged his nerveless body into my grasp and then, fortunately clearing the rail and the pounding wheels, I flung him to the right of way. Again Providence intervened. The train was thundering over the crest of a high embankment and when I let go of London, he rolled down a grassy slope.

The next instant I was ready to repeat his vault for life. But ere I let go of my hold on the handle of the car’s sliding door, I glanced back into the inferno produced by the pendulum of death. Most timely had we accomplished our exit! The flying weight was bending the gunnels as if they were chaff: Exactly overhead of where we had lain huddled, hand-sized splinters were easily ripped off the car box by the cavorting railroad link.

Then I leaped—a leap with life or death at stake. I performed a neat line of somersaults and did other acrobatic stunts ere, like Jack London had before me, I, too, was deposited at the foot of the grass-covered incline. There we both lay sprawling but uninjured. But so terrific was the horror we had passed through that it was some while before we could shake off the grip of our experience.

“And say, A. No. 1, didn’t we make a hair’s breadth escape from the finish of all things mundane?” gasped Jack London when finally he had recovered so far as to connectedly express his thoughts.

“The Road provides its devotees with such a grand array of dangerous entertainment, one chasing the other so close at the heel, that it is but a matter of days for the hobo to reach the end of his lifetime,” I commented contemplatively.

“That’s so!” he blurted out and then a weak smile spread over his wan face, indicating that he, too, comprehended the absolute hopelessness of the existence we were leading.

“The Killing of the Goose.”

We walked to Graytown. There we stopped for brief rest and improved the opportunity by striking out to panhandle a meal. My lunch was earned by trimming the acre-sized lawn of a residence. Returning to the railroad station, which by way of mention, is the pre-arranged meeting place of all hoboes traveling in company, I waited for the coming of Jack London. More than an hour had elapsed ere he arrived at the depot.

“Been having troubles connecting with a handout, sir?” I gruffly quizzed, having completely lost my patience because of the long wait and the fact that several “good” freight trains had stopped and then without us had departed from Graytown.

“None whatever!” he reported, speaking as if he resented my insinuation of his being incapable of properly looking after his wants. “Contrariwise, while I was absent, I was continually making away with a really firstclass meal.”

“Tackled a drummer who treated you to a hotel course-dinner which took an hour to finish?” I came back, believing I had struck a straight clew as commercial travelers were about the best fellows going.

“No, my angel wasn’t quite up to the generosity of the drummers! Nevertheless, I spoke the truth.” London laughed, and when I insisted on hearing the details of his experience he reviewed a bit of “human interest” of the first rating.

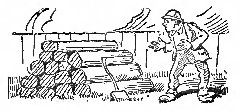

“There’s a woodpile in the back yard and you’ll find an ax hanging on the wall of yonder wood shed, sir!” Jack London was advised by the mistress of a residence where he had applied for food. “And only when you have split a sufficiency of kindlings to have earned your meal, shall I call you to the stoop of the kitchen. But if this arrangement does not suit you, you have the privilege of continuing on your way.”

“But, as I was saying, I am starving, marm!” rejoined the vagabond, a plea which proved of no avail as the pertly spoken woman sharply shut the door in his face, permitting him every chance to select his choice of either of her propositions without being embarrassed by her presence.

Tramps, especially while en route, cannot well afford to miss a meal, even though a task is connected with its acquirement. Too, the outdoor existence is a most phenomenal appetizer. Therefore Jack London accepted the wood chopping job which the lady of the house had set for him as a means of earning his dinner.

He went to work with a will to reduce the size of the wood pile. This proved quite an undertaking. The material he tackled was cordwood cut from live oaks, thoroughly seasoned in the heat of the summer—a process which had still further toughened the stringy fiber of the hard wood. The ax was not of the sharpest. Yet he persevered as he was buoyed by a hope that the meal would prove commensurate with the great exertions he expended while making a scarcely noticeable inroad on the cordwood.

Then he came to his first surprise. It was in the person of the lady of the residence who interrupted him at his task by arriving with a plate on which was placed a succulent roastbeef sandwich smothered with gravy. She remained until he had partaken of the tidbit. While she retraced her steps, he attacked with renewed vim the hearts of oak. Then for a second time she returned to regale her woodchopper with a plate of tasty soup. When she came for a third time, she brought a saucer of delicious salad. Repeating her trips, she gradually fed him a full meal of the best cookery. Finally, she sweetly informed him, that the task he had performed sufficed to settle for his repast.

“Would you mind telling me why you fed me the dinner piecemeal, marm?” inquired Jack London before he took his leave.

“But ... and, well ... I don’t care to take a stranger into my confidences, sir!” she blustered, evading an answer.

“Suppose I would appreciate the information, marm?” persisted Jack London, undaunted by her refusal.

“Then you insist that—” she had halted in her sentence and while her cheeks flushed, she acted as if she debated with herself if or if not to tell him, then she went on: “I fed your dinner in courses as this morning a hobo who preceded you here ate his meal and then ran off without touching the ax, though this day, more than ever previously, I needed kindlings for the starting of fires!”

“Verily, verily! Among ourselves we hoboes are our worst enemies!” mused Jack London as he went from the house to meet me at the railroad station.

“Shadows of the Road.’

At midnight and soon after we had wearily trudged into Air Line Junction, the division freight train terminal located just beyond the boundary of the city of Toledo, the fair weather which had prevailed for so many weeks abruptly changed to a drizzly rain that held on.

Rain-stormy days and, more especially, such nights as this one was, were ideal time for the hoboing of railroads. Then detectives and other implacable foes of the Wandering Willies have retreated from track and train to their lairs—yard or station offices or, if overtaken en route, cabooses or engine cabs.

The downpour had assumed torrential proportions when a freight train departed from the yard. We scanned the cars while they passed us to find a shelter aboard from the miserable weather. Through the gloom of the night we saw a small end door of a box car to be standing ajar. Mounting to the bumpers of the car, we took note by the flickering light of a match we had struck that the contents of the car was lumber. Evidently an amateur had attended to the loading of the cargo, for while the boards were stacked upwards until flush with the ceiling, a large space remained vacant at the side of the car from where we surveyed its interior.

Momentarily the train was gaining speed. The box car, but partly loaded, looked most inviting for a ride through the rain-riven night. Without further delay we climbed aboard. Right then a series of tribulations commenced. The door through which we had entered would not shut. Not even when we pulled and pushed at it with might and main. Neither would it budge when we had returned to the bumpers and there repeated our efforts from outside the car. Finally, after we had wasted the last of our matches, the blackness of the night thwarted a successful search for the cause of the clogging of the door.

Crawling back into the car, only too soon we were to become aware that it offered but a most indifferent shelter from the unfriendly elements. In a corner and farthest from the spot where the rain driving in through the open end door splashed to the floor, we pitched our berth. The track was a straight-away one for many miles beyond Toledo. Then came a curve which routed the train to run in a direction which brought the downpour pattering against our cheeks. This, naturally, sharply aroused us from our sleep. We scurried for shelter to another corner. But soon another curve sent the storm into our new retreat. There were other curves and more changes of our berthing. We gave up all further attempts to snatch a rest when the floor of the car had begun to resemble a miniature pond.

The train made a first halt at Ryan where it stopped to take on water. During this interim in the journey, two tramps came to keep us company. The newcomers had searched the whole length of the train to find shelter. At the next stop another pilgrim of the Road joined our crowd. Later on, where the train entered a siding, five other tramps were added to our hobo club. Others came and some more until no less than a score of bedraggled tourists were squeezing each other in a space which now became very narrow quarters.

One of the rovers carried a flash lantern. While he undertook to search for the fault which prevented the sliding of the door, I recognized him to be a fellow badly wanted by the police. He removed a splinter of wood that had become tightly wedged in the runway. Obviously, it was placed there by a hobo who feared to be trapped by the shutting and fastening of the door.

While jockeying to provide a favorable position for his train at the Butler (Indiana) coal chute, the engineer slammed the brake shoes with such a sudden force against the rims of the wheels of the cars which were provided with automatic brakes that the remainder of the train was given a most terrific jolt. This sudden shock completely disrupted the natural adhesion supplied by heavy weight to the lumber stowed in our car. The hefty boards were hurled forward with a momentum so great, that some of the hoboes were mercilessly wedged against the sides of the freight car. With others of our fellows who had come through the accident without sustaining serious harm, we extricated ourselves from the tangled mass of jammed timbers and crushed humans. Then we beat a quick escape into the open.

Extraordinarily precipitate was our exit from the box car. Actually we fairly fell over each other to be first to reach the right of way, so anxious we were to remove ourselves promptly from the vicinity of the mishap. We feared an. interference with our travel plans and other inconveniences should the authorities decide to hold us as witnesses or, and this was likely, to punish us for trespass.

While Jack London and I scurried for cover, we heard ringing through the darkness the piteous cries of the unfortunates whom in their agony we others had shamelessly deserted. Still we went on—we did not care to get mixed up with new trouble. Then, by chance, while we looked back, we saw how a gleam of light brightly lit up the interior of the car we had quit in such cowardly haste. This brought us to our senses. Responding to the urgings of our outraged consciences, we decided to return to the car and help with the rescue of the injured, irrespective of the outcome of such a step.

Although we were running on an errand of mercy, impelled by a natural suspicion to which every hobo is heir, we took every precaution to guard against untoward surprises. Stealthily mounting the bumpers, we peeped into the end door of the lumber car. We discerned neither officers nor railroaders in the freight car. Instead we saw by the light of his flash lantern that the yegg, he who was hunted for by the authorities, was busily working over the injured. He was not offering succor to those who with their own bodies had become the living cushions which had saved him from sharing their fate; quite to the contrary, he was rifling their pockets of the pitiful contents one might expect in possession of penniless hoboes.

Slipping back into the night we hurriedly held a council of war. Well aware that all murderous hobo criminals carried concealed weapons, we decided against giving battle to the degenerate. Instead we ran to the railroad depot which was located nearby.

There we acquainted the night-operator with the particulars of the crime. He promptly gathered a posse. But ere the avengers closed in, the yegg had escaped from the car from which soon afterward an ambulance hauled away several loads of battered hoboes.

When the train departed from the coal chute, on account of the hard rain, we climbed back into the lumber car. But this time we crawled a-top of the cargo where the shifting of the. timber had left an ample space. But before we allowed ourselves to drop off to sleep, we barricaded our berth in such manner that we were secure against accident or other interference. By taking this precaution we merely proved that we had practically mastered the lesson of not putting a further trust in an adhesion to each other of either the boards of the lumber or the vultures of the Road.

“Old Strikes & Company.”

Even before the train was running under a fair headway again, Jack London and I had sunk into sound slumber. From our rest we were awakened by loud commands, roughly spoken. Some one ordered our obedience to the law. Instinctively almost, we realized that we were trapped in the side-door Pullman by a police officer as our fellow-hoboes previously had been by the unstable cargo.

But while we were asleep, at stops and grades there had swarmed into the car a new lot of tramps. By the gray light of dawn we saw that the forepart of the car was packed with hoboes like a can with sardines. These rovers hastily complied with the mandate of the John Law. Their crowding to and crawling through the narrow aperture of the end door obscured the interior of the car to the view of the officer. Grasping our opportunity, Jack London and I wriggled back over the boards and dropped from sight into the vacant space left to the rear of the lumber by the shifting of its upper layers.

As it was, the captor of the others never suspected our presence. Laying low in our retreat, we heard him herding and then leading his prisoners away into captivity. Only some time after the lightest of noise had died away in the distance, we dared to emerge from our hiding place.

Rightly it is said that no blessing comes to him who trespasses on railroads! Our glee that another time we had escaped the just due of the law, proved of brief duration. Scarcely had we landed on the ground, than we heard some one hail. When we gazed about to see what was wanted and by whom, we recognized in the person of him who had hailed, “Old Strikes.”

Some time or another, but in most instances no end of times, every hobo roaming at will over the land had been forewarned against Old Strikes. Approaching Jeff Carr of Cheyenne in fearless ferocity when it came to dealing with John Tramps, he too was conceded by the latter to be one of their most relentless persecutors. By natural gravitation he came to his abounding dislike for everything affiliated with tramping and trespassing. In his day he had been a car inspector. While searching over the cars for needed repairs, he came in frequent contact with every species of the hobo. Therefore, it could not have been otherwise but that a great chasm of hate should have sprung up between him who earned his bread by the sweat of his brow and they who were pure and simple parasites of humanity and who everlastingly and most maliciously sneered at every toiler. One day he chose to vent his spleen on a box car tourist who had given cause for punishment. But the car inspector ran up against a losing proposition when he tackled the tough—he came out second-best from the fracas which ensued. This humiliating defeat at the hands of one who belonged to a class he hated so cordially, added fresh fuel to the great malke he bore even then towards hobodom. Finally, he resigned from his job and was readily granted his request for a transfer to the position of a yard watchman in the division freight terminal at Elkhart, Indiana.

There was left no possibility of committing an error in our identification of him who had hailed—hailed us, at that. He was Old Strikes and could be none other. A scarce three car-lengths away he came running, affording a clear view of his person. He was viciously whirling overhead a short span of heavy dog chain. To insure its presence under all circumstances, this chain was securely fastened to his right wrist. Of all police representatives abroad in the land and waging a merciless war against hobodom, Old Strikes was the only one who had adopted this unique device as a means of attack and defense. His selection of this distinctive weapon came only after he had personally passed through a number of holdups by hoboes—who mark the sting of complete disgrace—had relieved him of his six-shooters and other approved protectives.

And then Old Strikes yelled for us to light out. While we gazed at him for the moment undecided which course to pursue we noted a decided slackening in his running gait. Fellow-tramps had cautioned us to beware of his practice. He preferredly allowed his prospective victim to run away ahead of him. This sly procedure abridged all argumenting and rendered his prey incapable of offering resistance. Closing in from the rear, he would strike him who was fleeing from the avenger of the law a crushing blow with the heavy chain. So expert had he become by constant practice with this, his favorite weapon, that never was a second stroke required, not even when it came to an effective felling of the burliest of the trespassers. When he had scored the knockout, and then only, he troubled himself to institute inquiries as to the business which had brought the vanquished to prowl on the premises of the railroad.

Despite the manifold advance information we had received concerning the methods used by Old Strikes, we lit out like frightened hares. Ours was a case of instinctive self-preservation, for it was the first law of Nature that supplied the overpowering incentive which urged our feet to run their fastest in an attempt to score a getaway where most hoboes before us had miserably failed. Fortune favored our exit! Well rested as we were by the sound slumber we had enjoyed, we managed to break the record by getting ahead of Old Strikes to and then over the right-of-way fencing. There we were free of molestation at the hands of our enemy, for the fence abrogated the rule of the wielder of the dog chain as his authority was strictly demarkated by the limits of the property controlled by the New York Central.

Although for a while we were quaking like aspens during a storm from our fright and the great exertions of the race we had run, we quickly returned to a normal state of mind. Then elated by our success, we retaliated by mercilessly gibing Old Strikes on his signal failure to accord us the treatment which had earned him the nickname he so well deserved. In his helplessness he promised, provided we placed ourselves where he could legally enact his threat, to regale us to the best in the line of strikes his chain was capable of delivering under his masterly guidance.

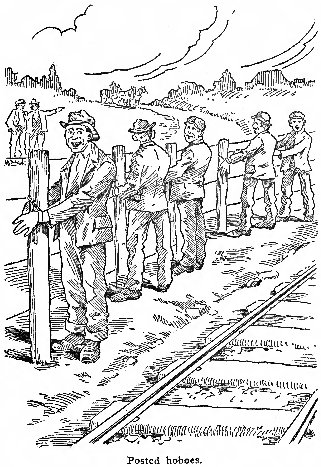

We left the John Law and took to a highway which led off in the direction of Elkhart. This public road closely paralleled the railroad. Perhaps a mile from where Old Strikes still lingered by the fence, keeping an alert tab on our actions, a most comical sight greeted us. The highway at this point was less than a hundred yards from the railroad fencing. There strung out in a long line we saw no less than thirty men. They were hugging the posts of the fence, one fellow to each post. Though they behaved livelier than an equal number of fleas, yet they held to their queer embrace of the fence supports. Further, while we stood amazedly sizing them up, we could plainly overhear the bantering remarks they passed to each other as to who of them would be the first to quit his job. Despite their jesting and quite contrary to the dictates of common sense, none of the post huggers made a least effort to desert his most ridiculous position.

Jack London judged the strangers to be lunatics who, so as to have them out of the way for the day, were allowed to follow the inclinations of their unsound intellects.

“Let us step to closer quarters for a better observation of their singular antics, A. No. 1!” my hobo mate urged, a suggestion to which I conceded.

Believing that we were about to carry our safety in our hands, we warily, approached the strangely acting fellows. Nearing their station by gradual stages, we quickly comprehended the aspect of the game they played or, rather, the one of which they were the pawns. They were enacting the role of another of the countless tragedies one continually encountered at almost every nook and turn of the Road.

The unfortunates were trespassers who in the course of the preceding night were rounded up by the police patroling the freight terminal. They were tramps and out-of-works indiscriminately taken into custody. For the want of a more convenient and, perhaps, less exposed detention the officers had taken recourse to the right-of-way fencing for herding their prisoners. With handcuffs the hoboes were manacled to the fence posts. To forestall a “jail delivery,” one of each pair of steel bracelets was passed through the stout wire meshing and then around a support of the fence. Besides these whom the John Laws had tangled up with law and the fence, not a soul was to be seen. But while we studied to find means to liberate the hapless chaps from their uncomfortable quarters, a large farm wagon drove into view.

This wagon was drawn by a team of horses. When abreast of where the hoboes stood staked out in the open, the horses were allowed to move the vehicle at a very slow walk only. One of the two occupants—they were John Laws as their subsequent actions proved—climbed down off the wagon and then stepped over to the side of the fence. There he gingerly released a trespasser from a picket and then re-adjusting the handcuff, he sent the unfortunate to the wagon where the other officer saw him to a seat. Thus man after man was released from his awkward position, one which with certainty must have become a most exquisite torture to those of the offenders who since dusk had decorated the fencing. Soon the hoboes were collected in the wagon which then, running at a smart jog, left for Elkhart, a distance of several miles.

Returning to the highway, Jack London and I resumed our walk. It was breakfasting time when we arrived in the more thickly populated suburbs of the city. There we separated to mooch our morning meals. Later on we met at a street corner.

When once more we were walking in the general direction of the railroad station, Jack London regaled me with the details of an adventure he ran across while he was hunting for his breakfast. Refused food at the doors of the well-to-do and the rich and the very wealthy he had hied himself to the homes of folks in humble circumstances. There a lady had in a friendly way invited him to share the morning meal of her family.

The Samaritan in petticoats was a poor washer-woman. To still further enhance the glory of her charity, she was a widow who had six children left on her hands. None of her youngsters had arrived at an age where they might have at least lessened the burden which an unkind fate had so heavily thrust upon the shoulders of their frail mother. But on this behalf she voiced no complaint. She owned her home, though it was a miserable frame shack. But it was a heaven to her and her little ones as there they were protected from the landlords who relentlessly hounded other poor ones for their dues. But she complained of a black shadow which effectively spoiled her life—an existence already so fearfully marred by hardest toil. She bittery lamented that at almost the same ratio she felt her physical strength waning while fighting the battle of life against the ever increasing expenditures made necessary by the natural growth and attendant outlays for her six, from year to year the total of her tax assessment was advancing at a most astonishing rate. She could give no sound reason for this increase of the general tax rating nor the amazingly mounting valuation of her humble abode and that of the patch of slum on which it stood. Construction of new residences and structures of every description was met with in every block, almost. New suburbs were taken in annually and had become contributors to the tax income of the city. Still every year had a larger tax rate—one guaranteed nevermore to mount—and new taxing schemes and ever heavier assessments, exactly as if the locality suffered in the throes of a great national calamity. Thus ran the plaint of the widow.

There and then we had a hearty laugh at the expense of others—they who were encumbered with real estate and other taxable property. We were of the improvident. We were tramps—just plain hoboes.